THE JEWS OF PACOV REMEMBERED

IN FAIR LAWN, NJ

PREFACE

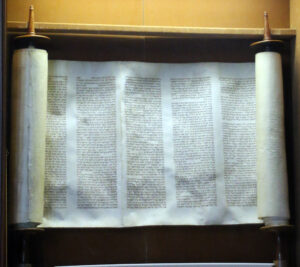

The text below is the official certificate from the Memorial Scrolls Trust at the Westminster Synagogue, London about the Torah from Pacov that is on long-term loan to our synagogue, The Fair Lawn Jewish Center/Congregation B’nai Israel in Fair Lawn, New Jersey. The Scroll is in a display case in our Main Sanctuary and this certificate is in a frame below it. The Memorial Scrolls Trust asks us to make, “Each Scroll… a messenger from a martyred community that depends on its new community to ensure that their heritage is cherished as well as their remembrance as individuals.” This booklet is part of our ongoing commitment to preserve the memory of the Jewish community of Pacov.

The Sefer Torah Number 74 which this certificate accompanies is one of the 1,564 Czech Memorial Sifre Torah which formed part of treasures which were saved by being collected in Prague during the Nazi occupation 1939 – 1945 from the desolated Jewish communities of Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia, and which then came under the control of the Czechoslovak government for many years.

The scrolls were acquired, with the help of good friends, from Artia (the Czechoslovak State Cultural Agency) for Westminster Synagogue, where they arrived on the 7th February 1964.

Some of the collection remains at Westminster Synagogue, a permanent memorial to the martyrs from whose Synagogues they came; many of them are distributed throughout the world, to be memorials everywhere to the Jewish tragedy, and to spread light as harbingers of future brotherhood on Earth; and all of them bear witness to the glory of the holy Name.

This Scroll came from Pacov and was written in 1900.

Fair Lawn Jewish Center/Congregation B’nai Israel

December 1978This Scroll is the property of the Memorial Scrolls Trust.3

INTRODUCTION

Rabbi Ronald S. Roth

Congregation B’nai Sholom/Fair Lawn Jewish Center

Fair Lawn, New Jersey

March 2016 – Adar II 5776

When we remember the Holocaust, we struggle to grasp the enormity of the death of six million individuals. Yet each of those individuals came from a city, a village or a town; each was part of a community.

It is my hope that this modest volume will preserve the memory of one small Jewish community, Pacov, in Bohemia. Jews lived and thrived there for some four hundred years. The community was never very large; at most there were a few hundred Jews in Pacov and the surrounding areas. They built a synagogue and obtained seven Torah scrolls. They provided for the education of their children. They worked in various trades and professions. Today all that is left is the cemetery, including a building that houses a memorial to that community, and the synagogue, now used as a warehouse.

That we, in Fair Lawn, New Jersey were able to preserve the memory of the Jews of Pacov was the result of a series of events. You can call them serendipitous, coincidence or part of a larger plan. For me there is a sense of fulfilling a larger purpose, preserving the memory of that community, and connecting ourselves to the lives of those who perished during the Holocaust.

The Fair Lawn/Pacov Connection

In 1978 two members of The Fair Lawn Jewish Center, Ed and Alix Davidson, obtained, on permanent loan for our congregation, a Holocaust Memorial Torah from Pacov. It had been taken to the Westminster synagogue in London in 1964, along with over 1,500 other Torah Scrolls from Czechoslovakia. A special case was constructed in our main sanctuary, where the Torah is prominently displayed. The certificate describing the scroll is the preface to this book.

In 2014, the 50th anniversary of the arrival of the Scrolls in London was celebrated. Each Jewish organization that had a scroll on permanent loan was asked to send a poster with a photo of the scroll to London for that anniversary celebration. Motivated by this milestone, I decided to do some research on the city of Pacov, working with the students of the Zayin (7th grade) class in the Howard and Joshua Herman Education Center, our Religious School. Google searches revealed that there are many photos of the synagogue as well as of the Jewish cemetery in Pacov. Further research, from the website of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington D.C., revealed photos, home movies and information about some of the residents of Pacov. The daughter of a survivor from that town, Gabi Rosberger, had donated them to the Museum.

Hoping for additional information, I tried to contact Gabi Rosberger. A Google search brought me to her Facebook page, where I left a message, but she did not answer. I kept checking there and concluded that she does not look at it. However, a note on the side of that Facebook page caught my eye: We have one mutual friend, Linda Shecter, who is a member of the congregation I served for twenty-two years in Nashville, Tennessee. I contacted Linda, who is an old friend of Gabi Rosberger from Montreal, and Linda shared Gabi’s email address with me. I was finally able to correspond with Gabi and learn more about her family and the materials she donated to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

More Google searching revealed that a photographer in the Czech Republic, Jitka Erbanov, had taken a number of photos of the synagogue and the Jewish cemetery in Pacov. That was during a photo trip to document Jewish monuments in that area. Several of them are in this booklet. I thank her for giving us permission to publish those photos.

During the commemoration of Yom HaShoah, Holocaust Memorial Day, at our synagogue in 2014, I prepared a PowerPoint presentation about our Torah from Pacov. The students in our Religious School worked on it as well. Our sources were the information and photos about Pacov on the internet.

Finding the Article and Its Translators

In addition to the photos and the materials about some of the residents of Pacov on the internet, I also found an article about the history of the Jews of Pacov written in Czech by Jan Zoubek, identified as an “archiver.” I mentioned to my congregation that I would like to have it translated. A member of my synagogue, Ellen Teitelbaum, told me she knows someone from the Czech Republic who lives in New Jersey, Daniela Hogan. Ms. Hogan agreed to translate the article. Without her great effort this booklet would not have been possible.

During my interactions with the Holocaust Memorial Trust, I was informed that as part of the agreement to have the Pacov scroll on loan, there is a requirement that we place a certificate next to the scroll. That original certificate had been lost. I sent a donation to the Trust and we received the document, framed it and placed it under the display case with the scroll in our Main Sanctuary in 2014.

In the spring of 2015, after a Shabbat morning service, I saw a couple reading that certificate and looking at the scroll. I introduced myself and they told me that they were guests at that morning’s bat mitzvah. One of them, Dr. Eva Horn, told me that she grew up in Prague and that her mother was a Holocaust survivor who lived through one of the horrible death marches that the Nazis forced concentration camp survivors to endure at the end of World War II. I told her about the scroll and asked, given that she knows Czech, if she might be interested in helping with our translation of the article about the history of the Jews of Pacov. She agreed. Her help in the translation has been invaluable and I am very grateful to her.

A Trip to Central Europe

In 2014 I led a group from my synagogue on a tour that included Prague, Budapest and Vienna. Several sights solidified my sense of connection to the Jews of Pacov. We visited Theresienstadt, a garrison town near the border of Germany and the Czech Republic. Jews from Bohemia and Moravia were deported there by the Nazis until they were sent to the death camps. We walked on the same paths and saw the buildings and barracks that Jews from Pacov knew in the final months of their lives.

In a synagogue in Prague the names of Czech Jews who were killed by the Nazis are listed on the walls, recorded town by town. I ran all through that building until I found Pacov and the names of its residents who died during the Holocaust. I was moved to see the names of families I had read about. I thought of their faces. They are familiar to me from the photos and home movies from the United States Holocaust Memorial website. We did not have time to visit Pacov but went to Trebic in Moravia. There we toured a restored synagogue and the narrow streets in the Jewish quarter that are, I assume, similar to Pacov.

On our last morning in Prague I was checking my email before packing my bags. I received a message from Karen Koblitz, a California resident whose family is originally from Pacov. She found out about my congregation’s Torah scroll from Pacov on the internet because it was the subject of an article in our local Jewish newspaper, the Jewish Standard. I began a correspondence with her. She was able to visit Pacov and sent me photos of the synagogue building. She is currently working to see if it can be restored.

Thinking About One Girl from Pacov

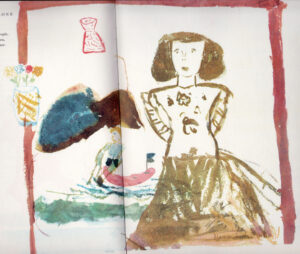

Gabi Rosberger told me that there is a drawing in the book I Never Saw Another Butterfly by her cousin Nina Lederová, whose last name is sometimes written as Nina Lederová. In that book of drawings by children in Theresienstadt, Nina’s artwork is described in the following way: “Nina Lederová was born, September 7, 1931,…deported to Terezin on September 8, 1942…Her last drawings…were done on May 9, 1944. Died in Oswiecim [Auschwitz] on May 15, 1944.’’ The picture was titled “Girl Looking Out of Window.” I am not sure how or why it was titled “Girl Looking Out of Window.” Did Nina give it that name? Was it proposed by someone else? Does it express her sense of being imprisoned in Theresienstadt?

While preparing the PowerPoint presentation about our Torah from Pacov, I was looking at that drawing with one of the students in our Religious School, Linit Freydenson. She pointed out something I had not noticed. There was a boy in what looked like a boat on the right side of the main figure. Considering that carefully and thinking of the photos of Nina and her brother Peter that I have seen, I propose a better name for that drawing: “Self Portrait by Nina Lederová with Her Brother, Peter.”

In the photos of Nina and Peter that survived the war, we see Nina with her hair parted in the center like the girl she drew. Her chin is shaped like the one in the drawing. I believe the “Girl” in the drawing is Nina. In one of the Lederer home movies taken in the 1930s that survived the war and has been posted on the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website, we can watch the Lederer family on a vacation trip to a lake with a boat. That drawing, I suspect, was a memory that Nina held dear, of a joyful time with her brother. Shortly after she finished that picture she was sent to Auschwitz where she, her brother and her mother were killed. I hope that this booklet will be a small way of recalling her and the lives of all who were murdered by the Nazis from the small but vibrant Jewish community of Pacov.

FORWARD

The Background of The History of the Jews of Pacov

by Jan Zoubeck

and The Historical Context

by Rabbi Ronald S. Roth

Pacov, pronounced “Patzov” and sometimes written with its German name, Patzau, is a small town fifty miles southeast of Prague. Today its population is approximately 5,000 and no Jews live there. The History of the Jews of Pacov, translated in this booklet, was written in Czech by Jan Zoubek, identified as an “archiver.” Mr. Zoubek was the manager of the municipal museum in Pacov and by profession a maker or seller of hats. The History of the Jews of Pacov was a chapter in the 1934 book Die Juden und Judengemeinde Bohmens in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart, The Jews and Jewish Communities of Bohemia in Past and Present by Hugo Gold. It was a companion work to Gold’s 1929 volume that contained the history of the Jews of Moravia. The territory of today’s Czech Republic comprises three historic regions, Bohemia, Moravia, and Czech Silesia.

The author, Jan Zoubek, clearly wrote this article working from the official register of the town, also known as the cadaster. It is not a work of critical history, yet it preserves the memory of those Jews who lived in Pacov for some four hundred years. He tells us about real estate transactions, the names of the Jewish families, their professions and the conflicts they had with other individuals and groups in Pacov. That gives us a sense of how the Jewish population of Pacov grew and what restrictions it faced as its numbers expanded. We read about legal disputes reflecting how different groups in the town saw their role in regulating Jewish economic life.

Jews first came to Bohemia in the tenth century. By the thirteenth century Jews were well established in communities in the fortified royal towns such as Prague. During that medieval period Jews had no citizenship rights. They could be expelled from their homes and from cities or countries by those in power. They might be seen as essential to the economic life of a community as traders and financiers, but they could also be considered competitors by the merchant classes. There were times of great cultural richness and times of total insecurity. There were clashes over control of the Jewish community and the taxes they paid to the local authorities. Jews could be held for ransom or a communal tax could be levied on them. However, the Jewish community was autonomous with taxes collected to support Jewish communal institutions. This is the “Jewish tax” that is mentioned in The History of the Jews of Pacov.

By the fifteenth century, shortly before Jews arrive in Pacov, there was a decline in royal authority. Jewish communities felt significant insecurity as different groups—the royalty, local nobles and the merchant classes—proposed granting Jews protection in exchange for monetary payment. There were also political and religious upheavals that affected Central Europe as the Holy Roman Empire became more decentralized. In addition, the merchant classes in many of the cities began to take over some of the commercial and banking functions previously done almost exclusively by Jews. Economic competition and religious zeal led to Jews being expelled from many of the larger royal towns.

In 1526 Bohemia and Moravia became part of the Hapsburg Empire, with the Jews being expelled from Prague in 1541. That decree was briefly rescinded, but in 1557 another decree expelling Jews from Bohemia was passed. Neither was fully enforced. We know that throughout the sixteenth century Jewish life continued to flourish in Prague. However, Jews left Prague and moved to smaller cities, towns and villages in Bohemia, often to be further from the centers of power. By 1600 half of the Jews in Bohemia lived in Prague, the other half in small towns and villages.

The Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) brought great devastation to much of Central Europe but did not undermine Jewish life in the region. Ferdinand II, who reigned from 1619 to 1637, protected and supported the Jewish community, and in 1623 affirmed all traditional rights of the Jewish community, guaranteed them freedom of residence, protection from expulsion and unrestricted trade and commercial activity throughout the kingdom. Until the reign of Charles VI Jews were the main traders in rural Bohemia and we read of several of them in this History.

Charles VI, who reigned 1711-1740, in 1726 issued the Familiants Law, limiting the number of Jews who could live in Bohemia and stipulating that only one son from any family could obtain the right to marry and establish his own family. This repressive law was intended to limit Jewish mobility and discourage the growth of the Jewish community. It was in effect until the Revolution of 1848. It forced Jews to settle in towns and villages where the nobility might protect them from the power of the state and again, no doubt, brought more Jews to Pacov.

In the eighteenth century the central state was relatively weak, but stronger in Prague. It was easy for Jews to disperse to small villages throughout the countryside. By 1724 Jews were living in approximately 600 small villages. By 1754 only one third of the Jews of Bohemia lived in Prague. That pattern increased so that by 1849 Jews in Bohemia lived in 1,921 localities. Only 207 of them had communities of more than 10 families and a formal synagogue. Only 148 of those communities had a minyan for Shabbat and holidays, the others being too small for that. Pacov was one of the communities that had a synagogue by the late nineteenth century and became a gathering place for Jews from the smaller communities surrounding it.

The Emancipation, the historical events that led to Jews having full civil rights as citizens of the countries where they lived, began in the Hapsburg Empire in 1781. It was gradual and uneven. There were edicts that allowed for religious toleration, partial liberation of the peasants from their ties to feudal lands, and the institution of compulsory elementary education. Many of these measures benefited the Jewish community; however, in some cases Jews were still restricted from owning rural property. Further liberal rules opened the doors of institutions of higher learning to Jews and in 1785 the judicial autonomy of the Jewish community in civil and criminal matters was ended. Only in 1841 were laws loosened on restrictions on the purchase of real estate by Jews, and on places where Jews could live. In 1867 Jews received full legal equality. By then many Jews had received a secular education. We read of conflicts over these rights in this History. Finally in the History, there is a list of Jews from Pacov who became prominent in Czech society. That reflects the integration of the Jewish community and also, we can assume, the weakening of some of the traditional patterns of Jewish life.

It is difficult to know the exact Jewish population of Pacov and its surrounding villages. This History speaks of the highest Jewish population as 164 in 1920. Yet The Encylopedia Judaica of 1906 lists the Jewish population of Pacov and 29 surrounding villages as 509. It notes that the community had a synagogue, a cemetery, a religious school and a “Hebrah,” a chevra kaddisha, the group that took care of the burial and traditional rituals for the dead. One can assume that the peak Jewish population of Pacov occurred sometime in the mid to late nineteenth century. That was before the general migration in Europe from small towns to large cities as a result of industrialization and increased commerce that offered opportunities to the residents of those metropolises.

What happened in Pacov during the Holocaust? Nazi Germany occupied Czechoslovakia in March 1939 and Hitler proclaimed the establishment of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia on March 15 of that year. There were many anti-Jewish measures that were carried out between 1939 and 1941. In October 1941 plans were made to deport 5,000 Jews from the Protectorate to Eastern Europe and to gather the remaining Jews of Bohemia and Moravia in Theresienstadt, an 18th century garrison town about 23 miles north of Prague. The mass deportations of Jews from Prague began in November 1941 and Jews in the provincial areas were registered starting in January 1942. The deportations from those provincial regions began on March 27, 1942. Before that date, all the synagogues were dissolved in those provinces. We know of one train that left Tabor, a regional city near Pacov, for Theresienstadt on November 12, 1942 with 650 Jews. Included with those deportees were residents of Pacov. In Tabor the Jews were transferred from the school to the train station and put on a train to Bohusovice, until 1943 the station nearest to Theresienstadt, where the deportees disembarked. They were then forced to march the remaining two miles to Theresienstadt. No doubt other Jews whose roots were in Pacov were sent to Theresienstadt from Prague or other larger cities. Of the 140,000 Jews who were transferred to Theresienstadt, approximately 90,000 were deported to places further east and almost certain death. About 33,000 died in Theresienstadt. Fifteen thousand children were sent there and ninety percent were killed in the death camps.

Jews lived in Pacov for approximately four hundred years. Its last Jewish resident was Jaroslav Lustig, the custodian of the Jewish cemetery. He died in 1985. Today that cemetery and a building at its entrance, sometimes called the “ceremonial hall,” remain. That “ceremonial hall” was where the chevra kaddisha, the burial society, prepared the dead for burial by washing the body and clothing it in shrouds. The synagogue building is still standing. The cemetery has been maintained, and the ceremonial hall contains an exhibit about the Jews of Pacov. The synagogue is in private hands. I have corresponded with several people who hope that the synagogue will become a museum and/or cultural center.

I have one simple hope for this slight volume. May it help to insure that the memory of the Jews of Pacov will endure.

HISTORY OF JEWS IN PACOV

Written by Jan Zoubek – Archiver, Pacov – [1934]

Translated by Daniela Hogan and Dr. Eva Horn

Edited by Lois Goldrich and Rhonda Roth

It is not easy to say when, and from where, the first Jews came to Pacov; and I regret the lack of information that would shed light on the hidden past. However, it is certain that Jews lived in Pacov years before we can see actual evidence of their presence there.

Most likely, Jews came sometime in the second half of the 16th century, after being expelled from Bohemia—mainly from Prague— in 1541. They arrived in large numbers and started settling in provincial towns. According to the lists created by Prague’s Jews in 1570 for tax purposes, only one Jew lived in Pacov. However, the probability is that this was not a single Jew but rather a whole family. The Jew in question made a living by trading merchandise, as was the custom of many Jews. Perhaps it is the same, unnamed Jew that sold the locksmith’s tools to Jan, son of Rozhurek, for 2 Meissner groschen (60 groschen) in 1596.

The first Jew known by name is Aaron from Pacov, who in 1622 leased work animals and wagons to those in the surrounding area. In addition to Aaron, at the time of the 30 Years’ War [1618-1648], there was another Jew, probably a descendant of the aforementioned Jews who lived in Pacov in 1570, the first recorded Jew in Pacov. This individual had a business trading just about everything — glass, brass, textiles, glittering knick-knacks, etc. After the battle on White Mountain [November 8, 1620], the situation of the Jews improved, particularly after they were put under the protection of the king in the year 1627. [Ferdinand III reigned from 1627 to 1657.] Lord Jan Cernin, Sr. from Chudenic, who owned the seigniorial Pacov, acknowledged and surely benefited from the Jews’ acumen. He wrote that “in the chaos of his time, only they are able and know how to get desired merchandise.” Lord Cernin conducted business largely with Jews from Prague. He sold them mutton from his farmsteads and bought diverse necessities from them and from the Jews of Tabor [a regional center city 18 miles west of Pacov or a reference to the larger Tabor district].

Jewish traders from Pacov had to pay the nobility both a monetary tax and a tax in kitchen spices. When, in 1638, a Jew in Pacov did not do so (not having spices in stock), the noble first intended to send him to jail. However, realizing that this wouldn’t serve his purposes, he released him after the Jew promised “he would go to Prague right away, travel night and day, and be back by Tuesday with the spices.”

Aaron from Pacov did not do very well. His cattle and wagon trade —which he had in addition to a store—was more of a hindrance than a benefit. The army took his cattle and wagons. Since the [Thirty Years’] war impoverished the farmers who owed him money, he became impoverished and did not have the money to pay taxes. Most likely, he is the Jew who in 1639 ran away from Pacov, leaving his debts behind. His father, unnamed, was, at the time, with his daughter in Destna [small town 19 miles south of Pacov].

Beginning with the second half of the 17th century, there is more information about Jews. From 1654, we finally have an accurate list of Jewish names. In 1640, Mr. Herschel, a tanner, bought a house from the nobility. Mr. Herschel had a helper named Salomon, not yet 20 years old. There was a second Jewish family composed of two brothers, Abraham and Joachim, who lived together and managed a store. A third family in Pacov was headed by a poor Jew, Filip, who owned a store that was not doing well. His son, Simon, and his servant, Moses, were both less than 20 years old. These three families had with them an unnamed Jew who taught the children. Only males above the age of 10 were counted for tax purposes; women and children were not included. Therefore, we can guess that the total number of Jews in Pacov was about 15-20 people.

The fact that they had a teacher for the children is an excellent testament to their vision and selfless devotion. In times of a deep cultural decline, they provided the children with an education, thus building a foundation for their future prosperity and growth. This is probably the reason why 80 years later, the richest inhabitants in Pacov were Jews.

Other news about Pacov Jews is random: For example, we know that in 1659, a soap boiler, Vaclav Stejskal, bought a small iron boiler from a Jewish woman for two reichsthalers; and in 1679, Alzbeta, daughter of Jiri Krepelka, quarreled with the wife of a Herschel until aldermen had to reconcile them.

After the 30 Years’ War, Pacov slowly recovered. Peace prevailed, and the sensible rule of General Sigmund Myslik’s (from Hirsov) widow, a countess from Zdar, [55 miles east of Pacov] created a calm environment. Therefore, in the second half of the 17th century the Jewish population grew and strengthened as well. The families named in the 1654 register lived together in two homes, Abraham’s and Filip’s house and Herschel’s house, bought from the nobility in 1640.

Due to an influx of Jews and natural, internal growth, two houses were insufficient. Probably newly arriving Jews rented from the nobility, originally Christian houses that were left empty after the country’s destructive depopulation. When they grew stronger economically, they bought those houses and the stronger Jewish community of Pacov arranged to have its own cemetery. They purchased the land for the cemetery—behind the town in the direction toward Rouckovice [northeast of Pacov]—in 1680 from the local municipality. They paid yearly interest of two groschen to the town.

One of the Christian houses that became Jewish property was a house named after the family Kolarik. A Jew, Abraham Pik, with his brother-in-law Benjamin, inherited the house from friends. Abraham then bought out Benjamin, and with the advice of his wife, sold the house on May 11, 1691, to his brother-in-law Salomon Posn and his wife for a sum of 43 Kopa, each Kopa being worth 70 kreuzer.

Salomon Posn, a Jew new to Pacov, had been renting a house from the nobility. He, actually, bought the house for his soon-to-be-married daughter and her future husband, intending to give them his rental home. During his purchase, he stipulated the right to sell the house to another Jew, should the wedding be canceled. The owner had to pay “Schutzgeld,” a fee for protection, as well as interest to the nobility, in addition to performing various obligations, such as helping with the harvest. For this he was paid 36 kreuzer yearly. Work was not hard then for the citizens of Pacov.

Another Christian house that came into Jewish hands, formerly known as the organist’s house, was built in a desolate place. The Jew Marek Bernard purchased the plot, of course without a field, from the organist Jiri Masata for four guldens. That house was built by the nobility, who sold it on July 28, 1701, for 75 gulden to Marek Bernard. Not only did he acquire the house and a plot of land for a total of 79 gulden, but, in addition, he didn’t have to pay anything to the town because he bought the house from the nobility.

Soon, Jews bought houses where there used to be butcher shops and where, possibly, they could have their own livestock. Prior to 1693, the tanner Salomon Abraham had a house in Pacov. Another tanner, as well as Vaclav Havlovy, a non-Jewish shoemaker, purchased houses next to his. It is said that Jews had lived in that house previously. It didn’t remain in Christian hands for long. Soon, Vaclav Havlovy sold it to Pavel Radec, also a non-Jew, who sold it to Salomon Abraham in the same year, 1693, for 25 Kopa. Salomon Abraham now had two small houses next to each other. The additional house was passed on by Salomon Abraham’s widow, Judita, on November 6, 1704, to his son Filip and his wife. The original Salomon house, formerly known as Jaros’ house—the one bought from the nobility for 70 Kopa Meissner—Mother Judita sold equally to sons Hasek, Filip, Jisa, and Pinkas for the same sum of 70 Kopa Meissner, on January 12, 1706.

The old house owned by tanner Filip since 1654 was sold in the year 1717 to the richest of Pacov’s Jews, citizen Jakob Lebl, for 150 gulden. In 1727 this house burned down in a terrible town fire. Jakob Lebl rebuilt it in the same location for 3,000 gulden. It was a real town mansion. It had three vaulted shops, a tavern, a granary, storage rooms, and two rooms on the second floor. On December 29, 1734, he registered the house in his and his second wife Rozalie’s, names, plus the names of children from his first and second marriages (his first wife was named Judita) – with one proviso. Should they die before his second wife, and should she remarry, her second husband would have no right to the house and all would belong to the children. It seems that his second wife was considerably younger.

Between 1654, when Pacov had only two Jewish houses, and 1722, the number of houses tripled. According to the Terezian cadaster, the tax register named after Maria Theresa [Hapsburg ruler from 1740 to 1780], the Jews owned houses from numbers 247 to 252.

House number 247 was occupied by the Jew Lazar (Leser) Haska. Born in Pacov, he was 28 years old and single in 1734 when Pacov revised its tax register. He lived with his widowed mother and siblings: sisters Rosina, 18 years old, and Lia, 14 years old, and 9-year-old brother Lebel. His parents were also born in Pacov. The house was formerly owned by the nobility, and he paid 16 gulden for protection and 3 gulden for taxes. He earned his livelihood by peddling various goods, mainly textiles, which he carried on his back to markets in the surrounding towns. On average, he earned about 100 gulden a year. At first glance, it does not appear to be much. However, it is substantial when we compare it to the average income of other Pacov citizens at the time, which was 40 gulden from farming or trade.

In 1722, in house number 248, lived the 26-year-old Jew Wolf R., with his wife Beta from Ronov. Wolf got married when he was just 15 years old. They had three children, Rosina, 10 years old, a son, Joachym, 6 years old, and 2-year-old Estera. His trade was selling linens, which yielded him 50 gulden. He paid 10 gulden to the nobility for protection and 6 gulden for the Jewish tax. Wolf ’s father Marek was born in Pacov, and, as we already know, he bought the house in 1691 from the organist.

House number 249 we already know as the house of Jarsovsky, but by 1722 it was known as Jisovsky. In 1734 it was owned by three brothers. The oldest, Salomon Jise, 45 years old, had a wife, Moscha, of the same age. Both were born in Pacov and thus weren’t among the newly arrived Jews. They had only two children, 22-year-old Filip and 15-year-old Lebl. The second co-owner, Pinkas Salomon, was born in 1704 and was married at age 17 to Pacov’s Jewish Ancka. By 1734 they had four daughters, Kacenka, 12 years old, Judita, 9 years old, Lia, 8 years old, and Rosina, 6 years old. In 1730 their son Filip was born.

The third owner, Salomon Haska, had a wife from Haber, from the Caslav district. They had a son, Kaska, and a 6-month-old daughter, Ancka.

The brothers claimed that their family was in Pacov for 70 years, from the time their grandfather lived there. That would mean the family Jise came to Pacov in 1660, making it the fourth oldest Jewish family living there.

Not only did they live together, but they worked together selling dry goods door to door. In their home in Pacov, they also sold textiles. The oldest, Salomon, earned 100 gulden, Pinkas, 75, and Salomon Haska, only 50. That made him the poorest Jew in Pacov. Each paid eight gulden per year to the nobility for protection, and three gulden each for the Jewish tax.

In house number 250 resided the richest man in Pacov, the Jew Jakub Lebl. His house, as we know, was rebuilt—after a town fire in 1727—for quite a large sum on an old Jewish site owned by Filip. Statistics in 1654 show the original house as belonging to his father. Jakub Lebl was, at that time, 45 years old. According to the 1734 records, he was married to his second wife, Rozalie, from Prague. He had total of seven children between his first and second wife. The oldest, Anna, was 15 years old; Jakob, 13 years old; Juttele, 10 years old; and Michal, 8 years old. Surprisingly, he also named his next daughter Anna. Then came Ludmila, 6, and Beta, Jakob Lebl was a wholesaler, buying wool in the surrounding areas and selling it to Pacov’s weavers. He then bought the finished textiles, selling them locally and internationally as far as Terst [modern Trieste, a seaport in Northern Italy]. From there he imported silks and silk ribbons. In his store, he also sold grains, spices, and trinkets. From the nobility he rented a distillery in number 246, with the rights to distill, sell, and tap spirits. His rent was 310 rynsky gulden yearly and 28 rynsky gulden for protection, which included use of the cellar. The older Jews in Prague estimated his ability to pay at a higher rate, and ordered a yearly Jewish tax of 96 gulden. His yearly profit, from the trade and a sale of spirits, was 1,000 gulden. That was a profit significantly higher than that of his Christian competitor, Mayor Matej Zoubek, whose business yielded him just 200 gulden. No Christian citizen in Pacov earned more than 200 gulden at that time.

House number 251 was inhabited by a Jew named Marcus Meller, born in Vimperk [about 75 miles southwest of Pacov]. He arrived in Pacov in 1702 and later married Regina, daughter of a Pacov Jew. This apparently took place in 1717, when he was 33 years old and his bride 28. They had only two sons, Lazar born in 1718, and Filip born in 1719. Marcus Meller purchased the house in 1718 from his brother-in-law. A tanner by trade, he rented a tannery from the nobility for 50 gulden a year. He also traded leather and wool. He paid 16 gulden 30 kreuzer for protection and a Jewish tax of 60 gulden. He, too, lived well, earning 300 gulden per year.

The last Jewish house is number 252. It was a Jewish house for many years and known in 1654 as Abraham’s house. It now belonged to Adam Mendl. He inherited the house from his father and lived in it with his wife, Marie, who was 10 years younger. In 1734 he was 50 years old, and they had no children. As did Marcus Meller, he paid 16 gulden 30 kreuzer for protection, and 20 gulden for the Jewish tax. He traded mainly textiles in local markets. That yielded him an income of 200 gulden.

In 1734 there is a mention of a prayer house. It was not a separate building, but rather was located in the house of one of the Jews.

It is understandable that the increase in the number of Jews in Pacov was not without controversy. What we know about these disputes is that they were not based on religious hatred but were genuine legal disputes emerging from the fact that Jews were buying “na gruntech,” properties that were meant to be taxed by the town, with additional fees paid to the priest. When Jews acquired them, they did not pay either the town or the priest. Pacov was the first town to claim its rights, and it won the lawsuit. In a 1718 settlement, it was determined that Jews living in the four now-Jewish houses were obligated to pay to the town a monetary contribution of 10 kreuzer per month. In the future, they would be exempt only if they bought empty building lots directly from the nobility. The Jews did not recognize the settlement and refused to pay. Only in 1729 did they promise to pay—and they did.

The dispute with the priest was more serious. He was complaining to a commission that his tithes decreased because Jews now owned previously Christian properties. From his point of view, he was correct. Tithes were tied to the houses, not the owner. He argued that he had a right to tithes from the four houses, and the Jews should pay.

The administration took on both complaints and suggested remediation. The commission—in Pacov, August 1734—recommended that Jews who insinuated themselves into the town after 1618 should be evicted from the town. (Note: The consensus decision of 1650 determined that in Czech lands, only Jews living there before 1618 were to be tolerated.)

As far as the town contributions were concerned, they recommended that the Jews start paying immediately the owed amount of 10 kreuzer per month to cover the period from 1718, when the town and nobility made a deal, until 1729, when they actually started to pay. Thus, the Jews needed to pay 80 gulden in total.

The commission was also concerned that the Jews did not live together, separately from the Christians, and instead lived scattered among them. There was a concern that this could give rise to disturbances, particularly when “the priest administers the last rites,” and it advised that the Jews should be ordered to move into new houses outside of the town (Tummelplatz). In addition, they should reconcile with the priest.

It is obvious that the commission’s initial recommendation to expel the Jews and move them out of town was not serious, as the eviction did not comply with the resolution of 1650. The Jews found the strongest support among the nobility, which was represented by a Prior of Pacov’s monastery, Barefooted Carmelites, Father Johannes Bernardus and S. Bonaventura. Surely, the noble was afraid of losing income from the protection fees paid by the four evicted Jews, which would have been 66 gulden 30 kreuzer. In addition, he might have defended them because of a poor relationship with the priest. He proved that the Pacov Jews had been in the town for 136 years and that they now held houses that were largely bought from the nobility. Therefore, they were “domicidal” and not subject to municipal taxes. He argued also that fees to the priest are not paid by Jews anywhere and that Jews lived among Christians in other towns like Tabor and Brandys, without causing any disturbance.

We do not know how it turned out, but it seems that from then on, the Jews paid the town, and they paid nothing to the priest. They kept acquiring more houses, and they started to live in a more concentrated area. In 50 years, they owned not six but ten houses. In Pacov’s register from 1787, they are listed in this order: I. Aristocratic Distillery, II. Bernard and Joachim Volff, III. Mendl Abraham, IV. Jakub Lebl, V. Isak Lebl and Abraham Moises, VI. Samuel Filip, VII. Salamoun Jakub, VIII. Lebl Elkan, IX. Jakub Jisa, and X. Filip Samuel.

In the 1829 register we find these Jewish homeowners in Pacov: Jakub Kral lived in a house number II. At this residence he also had a farm building. Salomon Moller had a residence in number III. In number IV, David Pick owned a very spacious house (I suspect it is the former house of Zelenohorsky, belonging at the beginning of the 18th century to Jakob Lobel). He also had a farm building. In number V lived Mojzis Robicek, and in number VI, Jakob Pick.

Abraham Rotenbaum owned houses VII and VIII. One of them was huge, 95 x 30 square sahu, or meters. Isak Randauer also owned two houses, numbers IX and X, but the smaller Jewish house, number I, was used by the nobility for a religious fund. Jews also owned urban houses, such as number 179, belonging to Mr. & Mrs. Lazar and Rosalie Moller. Gabriel Pick owned house number 174.

The Jewish religious community owned the synagogue in house number 379 and a plot of land, number 1379, measuring 200 square sahu, which served as the cemetery.

Before the upheaval in 1848, and before the total liberation and emancipation, the Jews had one more struggle. It was a long dispute with the city that was hindering them from free economic competition—and it was in vain. As before, the disputes were not driven by religious resentment but were consequences of a decline in the guild system.

Jews Emanuel Muller and Josef Moravec wanted to open stores and were granted permits in 1840 by the nobility. That caused an alarm and lawsuits followed, because on the demand of the guilds, the town refused to grant the permit to conduct business in the houses in the town. The municipal authorities successfully defended this fundamental principle at regional and county councils and, in 1843, even in a higher court.

The Jews did not want to yield on this, especially when the aristocracy was on their side. In spite of repeated rejections, Josef Moravec opened his store in 1840 in number 76. After closing the first one, he opened a leather store in 1842. Later that year, he received a permit from the manorial council to cut leather and cloth for sale. But again he was forced to retreat, because the city officials sealed his store, an action upheld by the court in 1843.

Equally unsuccessful was Emanuel Meller, who wanted to open a store in house number 274. The entire dispute was a struggle for jurisdictional power between the aristocracy and the municipality. Upholding the current laws, the municipality scored a victory, protesting that the aristocracy was interfering with its authority. The aristocracy could only grant permission to those Jews in houses under its jurisdiction. Both Jews wanted to open stores in municipal houses, which was impossible without municipal consent.

Another dispute was with the butcher’s guild in 1840. The Jew Jachym Moravec was leading a fight for free competition and to be incorporated in the guild’s books. The guild won. Jachym Moravec was not granted membership in the guild and was banned from selling meat.

A détente began after 1848, bringing total emancipation to the Jews and resulting in the strong growth of the Jewish population. The highest number of Jews,164, was reached in 1910. In 1929, due to World War I, this number fell to 121.

Among the outstanding Jews who lived in Pacov were Vilen Zirkl and Bernard Pick, JD. Vilen Zirkl was born in Jistebnice. He lived in Pacov briefly. He was an untiring Jewish-Czech worker, excellent theater actor, writer, and translator. He followed in the footsteps of editor Josef Penizek from national newspaper Naroni listy. He died prematurely from heart disease in 1894 and is buried in Pacov.

Dr. Bernard Pick was not born in Pacov but was a citizen there for 40 years. As a cosmopolitan intellectual with a large heart, and an idealist, friend, and advocate of ordinary people, Dr. Pick served for years in the municipal council. With his noble-minded character, he gained the deep respect and admiration of all who knew him. His biggest pleasure was to reconcile two feuding parties, often doing it for free. As a lawyer, he stood up only for cases he believed in.

Many other Jewish natives from Pacov deserve recognition: Emil Jokl, JD, minister of Postal Service and Telegraph; Hugo Jokl, Ph.D., professor of the Czechoslovak Komensky gymnasium in Vienna; Doctor of Engineering Josef Roubitschek; concert master Josef Moravec; and Mrs. Dolfina Pope, graphology expert, who wrote many valuable articles.

In commercial and industrial fields, the Jews in Pacov still occupy prominent positions. There is the Brothers Lederer’s large department store; and Victor Weiner’s leather factory, which began exporting goods to France, England, and Egypt even before the war.

The leadership of the Jewish religious congregation was entrusted to a progressive, forward-looking mayor, Emil Lederer. He was a wholesaler, who during his mayoral tenure corrected deficiencies necessary to reorganize the cemetery and to repair old tombstones.

A charitable donation of 4,000 Czech crowns was used to repair “Cadik-Hadin” hall, and preparations were started for the repair of the synagogue. The mayor also enabled the establishment of an exhibition, in Pacov’s museum, commemorating old Jewish artifacts, attracting the well-deserved interest of all visitors.

Photo 1 (above) Wedding portrait of a Czech Jewish couple, Rose and Robert Lederer. Rose later died in Auschwitz, and Robert, in Oranienburg.

Photo 1 (above) Wedding portrait of a Czech Jewish couple, Rose and Robert Lederer. Rose later died in Auschwitz, and Robert, in Oranienburg.

Photo 2 (opposite page) Three Czech Jewish children pose outside in front of a chain-link fence. Pictured are Nina and Peter Lederer flanking their cousin Ivan Rechts.

Photo 2 (opposite page) Three Czech Jewish children pose outside in front of a chain-link fence. Pictured are Nina and Peter Lederer flanking their cousin Ivan Rechts.

About Photos 1 and 2 Gabi Rosberger (born Gabrielle Reitler) is the daughter of Kurt and Blanka (Bruck) Reitler. Blanka is the daughter of Rudolf and Emily (Waldstein). Bruck grew up in Pacov, Czechoslovakia. Blanka’s father passed away in 1929, and her mother perished in Theresienstadt in 1945. Blanka had eight older siblings, three of whom died as children. The five who survived into adulthood were Erich, Victor, Lyduska, Rose and Henrietta. Erich was married to Rose and had one daughter, Lila. He passed away before the war, and his widow and daughter perished in the Lodz ghetto. Victor married Olga in 1934 and had one daughter, Ivanna (Eva). Olga passed away before the war, and Victor married a second wife, Mimi. They had one son, Rudolf. Victor, Mimi, Rudolf and Ivanna all survived the war. Lyduska (Lydia) married Tony Kares. They both perished during the war, probably in Auschwitz. Rose married Robert Lederer. They had two children, Nina (b. 1930) and Peter (b. ca. 1933). Robert died in a labor camp in Oranienburg. Rose and the two children were sent to Theresienstadt in September 1942, and from there, were deported to their death in Auschwitz on May 15, 1944. Rose could have been selected with Nina for work, but she refused to abandon Peter and insisted that all three remain together. As a result, they all perished. Henrietta married Joseph Rechts and had one son, Ivan. Joseph escaped to Palestine via Poland and Russia and planned to send for his wife and son when he reached safety, but they were deported before he could do so. They were sent first to Theresienstadt and then to Auschwitz where they perished. Blanka married Pavel Heller on August 17, 1940. When Pavel could no longer work as a Jew in Prague, they moved to the town of Plananad Luznici, where they rented a room from a Mr. Blazek. Pavel also went to work for Mr. Blazek, and the two became good friends. In 1942, when Pavel and Blanka were deported to Theresienstadt, they entrusted their family photographs and valuables to the Blazeks. Pavel was then sent to the front with the Czech army and never returned. Blanka remained in Theresienstadt and from there was deported to Auschwitz in 1943. She survived and returned to Czechoslovakia after the liberation. She resumed contact with the Blazeks, who returned her belongings. Soon after she met Kurt Reitler, who had survived the war in Shanghai. They both immigrated to Montreal and subsequently married. They had one daughter, Gabrielle. [Caption was provided by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum]

Photo 3

Photo 3

Photo 4

Photo 4

Photo 5

Photos 3, 4, and 5 The Jewish cemetery in Myslíkova Street leading eastwards to Hořepník, dates back to 1680. It is preserved as a Cultural Monument of the Czech Republic. There is a memorial to the victims of the Holocaust in the cemetery, (photo 4) and also a ceremonial hall with Hebrew inscriptions which houses an exposition about the history of the Jews in the area of Pacov. There are several hundred gravestones that can be dated as far back as 1796. Restoration work on the cemetery was done about 1983.

Photo 6 Hebrew inscription that was once above the gate of that building indicating that Meir Ya’akov completed repairs to this building on 1 Elul 5605, September 3, 1845.

Photo 6 Hebrew inscription that was once above the gate of that building indicating that Meir Ya’akov completed repairs to this building on 1 Elul 5605, September 3, 1845.

Photo 7 Photos 6 and 7 Interior of the Jewish ceremonial hall at the entrance to the cemetery in Pacov.

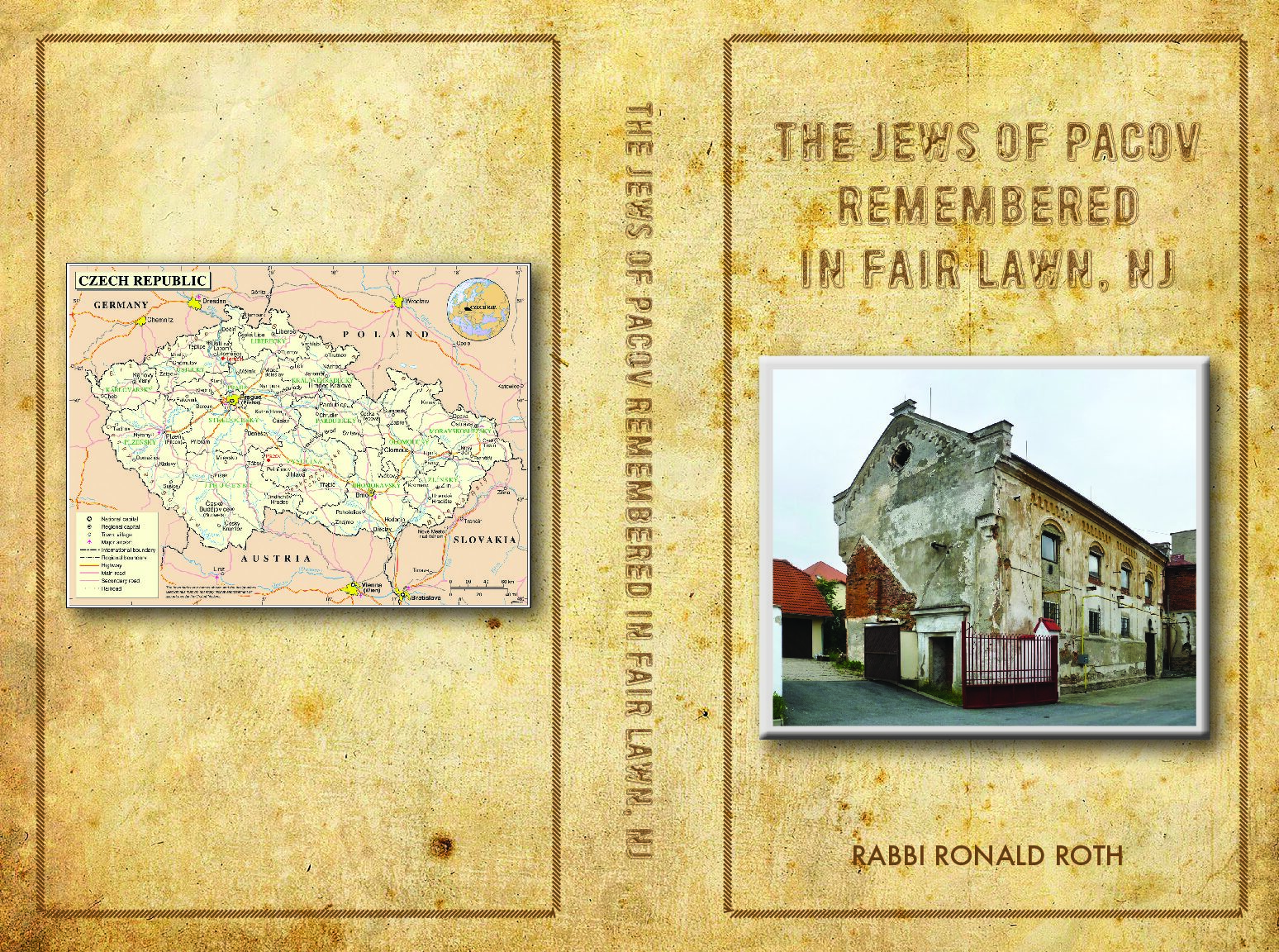

Photo 8 The former synagogue in Pacov stands in Jana Autengrubera Street as No 318, south of Svobody Square (Liberty/Freedom Sq.). After a fire of 1933 the building was remodeled, and since 1956 it has been used as a warehouse and is not accessible to the public. The house of the custodian, No 177, has not been preserved. Following the changes in the Czech Republic in 1989, the synagogue was sold to a private party in 1993.

Photo 9 Nina Lederer (Lederová’s) painting “Girl Looking Out of Window”

Photo 9 Nina Lederer (Lederová’s) painting “Girl Looking Out of Window”

PHOTO CREDITS

USED BY PERMISSION

Photos 1 and 2: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Gabriella Reitler Rosberger. United States Holocaust Memorial, p. 1 Desig #550.1851 W/S #47572 Museum Photo Archives CD # 0534, p. 2 Desig #550.1817 W/S #47579 Museum Photo Archives CD # 0543

Photos 3,4,5,6,7, 8 by Jitka Erbenová – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%C5%BDH_Pacov_04. jpg#/media/File:%C5%BDH_Pacov_04.pg33

Photo 10 Pacov Torah scroll on the wall to the right at the Fair Lawn Jewish Center/ Congregation B’nai Israel, Fair Lawn, NJ.

Photo 10 Pacov Torah scroll on the wall to the right at the Fair Lawn Jewish Center/ Congregation B’nai Israel, Fair Lawn, NJ.

Photo 11 Pacov Torah scroll at the Fair Lawn Jewish Center/Congregation B’nai Israel, Fair Lawn, NJ.34

Photo 11 Pacov Torah scroll at the Fair Lawn Jewish Center/Congregation B’nai Israel, Fair Lawn, NJ.34

NOTES ON SOURCES

I have drawn on the following sources as a basis for writing about the historical context: The best English source for a history of the Jews of Bohemia is in Languages of Community, The Jewish Experience in the Czech Lands by Hillel Kieval. A short version of that history is included in The Precious Legacy Judaic Treasures from the Czecoslovak State Collections edited by David Altshuler.

Both the Encyclopedia Judaica 1972 and the Jewish Encyclopedia, published from 1901 to 1906 and available online, have articles that I have used as references.

The websites of the United States Holocaust Museum, https:// www.ushmm.org/ and Yad v’Shem http://www.yadvashem.org/ have material about the Jews of Pacov.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I want to thank all of those who helped me to produce this volume: Ed and Alix Davidson who obtained, and literally brought the Pacov Torah to Fair Lawn; the two translators, Daniela Hogan and Dr. Eva Horn, without whose efforts I would not have been able to begin; Jitka Erbenova, who took many of the photos reproduced here; Gabi Rosberger, who donated to United States Holocaust Museum materials about her family from Pacov; Karen Koblitz, whose family is from Pacov and is working to preserve its synagogue building; Lois Goldrich, for her editing skills; Mindy Schultz, the graphic artist who designed this book; the students in the Zayin class of the Religious School of the Fair Lawn Jewish Center/Congregation B’nai Israel who helped search the internet for information about Pacov; and finally my wife, Rhonda, who edited, and corrected all my errors. I thank her for her skills, patience and love.

APPENDIX

The following list indicates where the Torah Scrolls from Pacov are currently located. This list was provided by the Memorial Scrolls Trust in London.

BASIC SCROLL CIRCLE FOR PACOV

Last updated 21st July 2014

NUMBER CONGREGATION TOWN

74 Fair Lawn JC Fair Lawn, NJ

235 Shore Parkway Jewish Center Brooklyn, NY

498 Temple Beth Torah Fremont, CA

584 Returned from South Africa to MST Museum 2014

970 Milton Keynes & District Synagogue Milton Keynes, UK

1032 Congregation Bnai Yisrael Armonk, NY

1163 Farmingdale Jewish Community Wantagh, NY*

#235 and #1032 have Facebook pages but no websites. The other communities all appear to have working websites through which one may find relevant contact information.

*A note from Rabbi Ronald Roth: I found out recently that three congregations, including the Farmingdale Jewish Center, listed here as the Farmingdale Jewish Community, merged in August 2012. That synagogue is called Congregation Beth Tikvah in Wantagh, New York.

RABBI RONALD ROTH was born in Far Rockaway, Queens and spent his childhood in Brooklyn, New York. He graduated from Cornell University with a BA in theatre arts and attended the Rabbinical School at the Jewish Theological Seminary, where he received an M. A. in Rabbinics and Rabbinic Ordination. He received an honorary doctorate from the Jewish Theological Seminary in 2005. Rabbi Roth has served Beth El Synagogue (East Windsor, New Jersey), West End Synagogue (Nashville, Tennessee) and Fair Lawn Jewish Center (Fair Lawn, New Jersey) during his 35-plus year career.

Rabbi Roth shares his love of Judaism and its teachings in myriad ways, with particular interest in outreach, education and Jewish ritual. There are many paths to commitment, he believes, among them looking to previous generations for inspiration and connection. This volume on the Jews of Pacov fulfills a desire to bring his congregation closer to a community and individuals who they do not know, but whose Torah scroll they see each time they walk into the sanctuary.